Abstract

The TOR (target of rapamycin) kinase limits longevity by poorly understood mechanisms. Rapamycin suppresses the mammalian TORC1 complex, which regulates translation, and extends lifespan in diverse species, including mice. We show that rapamycin selectively blunts the pro-inflammatory phenotype of senescent cells. Cellular senescence suppresses cancer by preventing cell proliferation. However, as senescent cells accumulate with age, the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) can disrupt tissues and contribute to age-related pathologies, including cancer. MTOR inhibition suppressed the secretion of inflammatory cytokines by senescent cells. Rapamycin reduced IL6 and other cytokine mRNA levels, but selectively suppressed translation of the membrane-bound cytokine IL1A. Reduced IL1A diminished NF-κB transcriptional activity, which controls much of the SASP; exogenous IL1A restored IL6 secretion to rapamycin-treated cells. Importantly, rapamycin suppressed the ability of senescent fibroblasts to stimulate prostate tumour growth in mice. Thus, rapamycin might ameliorate age-related pathologies, including late-life cancer, by suppressing senescence-associated inflammation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

06 April 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-021-00655-4

References

Vijg, J. & Campisi, J. Puzzles, promises and a cure for ageing. Nature 454, 1065–1071 (2008).

Kapahi, P. et al. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 11, 453–465 (2010).

Stanfel, M. N., Shamieh, L. S., Kaeberlein, M. & Kennedy, B. K. The TOR pathway comes of age. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790, 1067–1074 (2009).

Harrison, D. E. et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460, 392–395 (2009).

Campisi, J. & d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 729–740 (2007).

Acosta, J. C. et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 133, 1006–1018 (2008).

Bavik, C. et al. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms. Cancer Res. 66, 794–802 (2006).

Coppe, J. P. et al. A human-like senescence-associated secretory phenotype is conserved in mouse cells dependent on physiological oxygen. PLoS ONE 5, e9188 (2010).

Coppe, J. P. et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 6, 2853–2868 (2008).

Kuilman, T. et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 133, 1019–1031 (2008).

Orjalo, A. V., Bhaumik, D., Gengler, B. K., Scott, G. K. & Campisi, J. Cell surface-bound IL-1α is an upstream regulator of the senescence-associated IL-6/IL-8 cytokine network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17031–17036 (2009).

Baker, D. J. et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 479, 232–236 (2011).

Krtolica, A., Parrinello, S., Lockett, S., Desprez, P. & Campisi, J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12072–12077 (2001).

Liu, D. & Hornsby, P. J. Senescent human fibroblasts increase the early growth of xenograft tumors via matrix metalloproteinase secretion. Cancer Res. 67, 3117–3126 (2007).

Freund, A., Patil, C. K. & Campisi, J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 30, 1536–1548 (2011).

Vasto, S. et al. Inflammation, ageing and cancer. Mech. Ageing Dev. 130, 40–45 (2009).

de Visser, K. E., Eichten, A. & Coussens, L. M. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 24–37 (2006).

Glass, C. K., Saijo, K., Winner, B., Marchetto, M. C. & Gage, F. H. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell 140, 918–934 (2010).

Nathan, C. & Ding, A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell 140, 871–882 (2010).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899 (2010).

Franceschi, C. et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128, 92–105 (2007).

McElhaney, J. E. & Effros, R. B. Immunosenescence: what does it mean to health outcomes in older adults? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21, 418–424 (2009).

Coppé, J. P., Desprez, P. Y., Krtolica, A. & Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 99–118 (2010).

Freund, A., Orjalo, A., Desprez, P. Y. & Campisi, J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 238–248 (2010).

d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Living on a break: cellular senescence as a DNA-damage response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 512–522 (2008).

Beausejour, C. M. et al. Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO J. 22, 4212–4222 (2003).

Kortlever, R. M., Higgins, P. J. & Bernards, R. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a critical downstream target of p53 in the induction of replicative senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 877–884 (2006).

Wajapeyee, N., Serra, R. W., Zhu, X., Mahalingam, M. & Green, M. R. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell 132, 363–374 (2008).

Binet, R. et al. WNT16B is a new marker of cellular senescence that regulates p53 activity and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Cancer Res. 69, 9183–9191 (2009).

Chang, B. D. et al. Molecular determinants of terminal growth arrest induced in tumor cells by a chemotherapeutic agent. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 389–394 (2002).

Coppe, J. P., Kauser, K., Campisi, J. & Beausejour, C. M. Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29568–29574 (2006).

Krizhanovsky, V. et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 134, 657–667 (2008).

Novakova, Z. et al. Cytokine expression and signaling in drug-induced cellular senescence. Oncogene 29, 273–284 (2010).

Parrinello, S., Coppe, J. P., Krtolica, A. & Campisi, J. Stromal–epithelial interactions in aging and cancer: senescent fibroblasts alter epithelial cell differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 118, 485–496 (2005).

Dimri, G. P. et al. A novel biomarker identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 9363–9367 (1995).

Jeyapalan, J. C., Ferreira, M., Sedivy, J. M. & Herbig, U. Accumulation of senescent cells in mitotic tissue of aging primates. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128, 36–44 (2007).

Sedelnikova, O. A. et al. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 168–170 (2004).

Castro, P., Giri, D., Lamb, D. & Ittmann, M. Cellular senescence in the pathogenesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate 55, 30–38 (2003).

Collado, M. et al. Tumor biology: senescent in premalignant tumours. Nature 436, 642 (2005).

Ding, G. et al. Tubular cell senescence and expression of TGF-β1 and p21(WAF1/CIP1) in tubulointerstitial fibrosis of aging rats. Exp. Mol. Path. 70, 43–53 (2001).

Erusalimsky, J. D. & Kurz, D. J. Cellular senescence in vivo: its relevance in ageing and cardiovascular disease. Exp. Gerontol. 40, 634–642 (2005).

Martin, J. A. & Buckwalter, J. A. The role of chondrocyte senescence in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis and in limiting cartilage repair. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 85, 106–110 (2003).

Matthews, C. et al. Vascular smooth muscle cells undergo telomere-based senescence in human atherosclerosis: effects of telomerase and oxidative stress. Circ. Res. 99, 156–164 (2006).

McGlynn, L. M. et al. Cellular senescence in pretransplant renal biopsies predicts postoperative organ function. Aging Cell 8, 45–51 (2009).

Paradis, V. et al. Replicative senescence in normal liver, chronic hepatitis C, and hepatocellular carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 32, 327–332 (2001).

Roberts, S., Evans, E. H., Kletsas, D., Jaffray, D. C. & Eisenstein, S. M. Senescence in human intervertebral discs. Eur. Spine J. 15, 312–316 (2006).

Davalos, A. R., Coppe, J. P., Campisi, J. & Desprez, P. Y. Senescent cells as a source of inflammatory factors for tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 29, 273–283 (2010).

Schmitt, C. A. Cellular senescence and cancer treatment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1775, 5–20 (2007).

Schmitt, C. A. et al. A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell 109, 335–346 (2002).

te Poele, R. H., Okorokov, A. L., Jardine, L., Cummings, J. & Joel, S. P. DNA damage is able to induce senescence in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 62, 1876–1883 (2002).

Serrano, M., Lin, A. W., McCurrach, M. E., Beach, D. & Lowe, S. W. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 88, 593–602 (1997).

Ogryzko, V. V., Hirai, T. H., Russanova, V. R., Barbie, D. A. & Howard, B. H. Human fibroblast commitment to a senescence-like state in response to histone deacetylase inhibitors is cell cycle dependent. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 5210–5218 (1996).

Rodier, F. et al. Persistent DNA damage signaling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 973–979 (2009).

Rodier, F. et al. DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J. Cell Sci. 124, 68–81 (2011).

Choo, A. Y., Yoon, S. O., Kim, S. G., Roux, P. P. & Blenis, J. Rapamycin differentially inhibits S6Ks and 4E-BP1 to mediate cell-type-specific repression of mRNA translation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17414–17419 (2008).

Apsel, B. et al. Targeted polypharmacology: discovery of dual inhibitors of tyrosine and phosphoinositide kinases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 691–699 (2008).

Parsyan, A. et al. mRNA helicases: the tacticians of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 235–245 (2011).

Feoktistova, K., Tuvshintogs, E., Do, A. & Fraser, C. S. Human eIF4E promotes mRNA restructuring by stimulating eIF4A helicase activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13339–13344 (2013).

Demidenko, Z. N. et al. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 8, 1888–1895 (2009).

Sun, Y. et al. Treatment-induced damage to the tumor microenvironment promotes prostate cancer therapy resistance through WNT16B. Nat. Med. 18, 1359–1368 (2012).

Chang, B. D. et al. A senescence-like phenotype distinguishes tumor cells that undergo terminal proliferation arrest after exposure to anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 59, 3761–3767 (1999).

Sheiban, I. et al. Next-generation drug-eluting stents in coronary artery disease: focus on everolimus-eluting stent (Xience V). Vasc. Health Risk Manage. 4, 31–38 (2008).

Ciuffreda, L., Di Sanza, C., Incani, U. C. & Milella, M. The mTOR pathway: a new target in cancer therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 10, 484–495 (2010).

Meric-Bernstam, F. & Gonzalez-Angulo, A. M. Targeting the mTOR signaling network for cancer therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 2278–2287 (2009).

Xue, W. et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 445, 656–660 (2007).

Finkel, T., Serrano, M. & Blasco, M. A. The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature 448, 767–774 (2007).

Huang, S., Bjornsti, M. A. & Houghton, P. J. Rapamycins: mechanism of action and cellular resistance. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2, 222–232 (2003).

Weichhart, T. et al. The TSC-mTOR signaling pathway regulates the innate inflammatory response. Immunity 29, 565–577 (2008).

Hayward, S. W. et al. Establishment and characterization of an immortalized but non-transformed human prostate epithelial cell line: BPH-1. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 31, 14–24 (1995).

Bae, V. L. et al. Metastatic sublines of an SV40 large T antigen immortalized human prostate epithelial cell line. Prostate 34, 275–282 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Rogers, B. Kennedy, G. Lithgow, S. Melov and members of the Campisi laboratory (Buck Institute) for comments and discussions, I. Coleman for assistance with figure preparation and data analysis, and R. Strong (U Texas Health Science Center) for providing the rapamycin encapsulated chow. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AG045288 to R.-M.L., Hillblom Medical Foundation (CP), NIH T32 training grant AG000266-16 to K.A.W.-E., NIH grants CA143858, CA155679 and CA071468 to C.C.B., NIH grants AG032113 and AG025901 to P.K., DOD-PCRP grant PC111703 and National Natural Science Foundation of China 81472709 to Y.S., NIH grants CA164188, CA165573 and CA097186 and the Prostate Cancer Foundation to P.S.N., and NIH grants AG09909 and AG017242 to J.C. and AG041122 to J.C. and Y.I.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.-M.L., Y.S., A.V.O., C.K.P., A.F., L.Z., S.C.C., A.R.D., K.A.W.-E., S.L., C.L., M.D. and P.L. acquired and interpreted the data. M.J. analysed rapamycin concentrations. G.B.H. and Y.I. provided pathological assessment. R.-M.L., Y.S., C.C.B., P.-Y.D., P.K., P.S.N. and J.C. designed experiments and interpreted data. R.-M.L., Y.S., P.-Y.D., P.K., P.S.N. and J.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

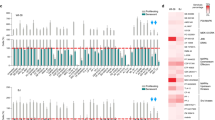

Supplementary Figure 4 Rapamycin suppresses the SASP in multiple cell strains and lines.

(A) IL-6 secretion by IR-induced senescent cells, normalized to replicatively senescent IMR-90 normal fetal lung human fibroblasts. Shown are WI-38 normal fetal lung fibroblasts, MCF10-A and 184A1 immortal human breast epithelial cells and PSC27 normal adult prostate fibroblasts, treated with either DMSO (blue bars) or rapamycin (red bars). (B) We treated non-senescent (NS) HCA2 cells with rapamycin for 6 days, collected CM and analyzed IL-6 by ELISA. IL-6 secretion by irradiated senescent cells (Sen (IR)) is shown for comparison. (C) Immunofluorescence staining for 53BP1 was compared between NS and senescent (Sen IR) cells treated with DMSO or rapamycin (one representative image is shown). (D) We determined the number of foci in NS or senescent (Sen IR) cells treated with DMSO or rapamycin. With the exception of 184A1 experiment which was performed once, for panels A, B and D, shown is one representative of two or more independent experiments, each with triplicate samples. Raw data could be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Figure 5 The SASP is MTOR dependent.

(A) HCA2 cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs against GFP (shGFP; control) or one of three different shRNAs against raptor. Raptor transcript levels were measured and are shown relative the level in cells expressing shGFP. (B) HCA2 cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing shGFP (control) or one of three different shRNA against MTOR. The relative transcript level of MTOR was measured. (C) Normal HCA2 human foreskin fibroblasts, non-senescent (NS) or induced to senesce by IR, were treated with DMSO (control) or the indicated concentrations of the MTOR kinase inhibitor PP242. 7 days later, CM was collected and analyzed for IL-6 by ELISA. Values were normalized to the senescent cell level. For all panels, shown is one representative of two independent experiments, each with triplicate samples. Raw data could be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Figure 6 Rapamycin reduces SASP transcript levels and NF-kB activity in senescent prostate fibroblasts.

(A) Transcript levels of indicated SASP factors were quantified by qRT-PCR in NS and Sen (IR) PSC27 fibroblasts with or without treatment with rapamycin for 7 days. (B) NF-κB activity was measured after treatment with rapamycin for 7 days using a reporter assay. For all panels, shown is one representative of three independent experiments, each with triplicate samples. Raw data could be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Figure 7 FACS analysis of cell surface IL-1α.

(A) Flow cytometry for cell surface IL-1α was performed using NS or senescent (IR) HCA2 cells expressing shRNAs against GFP or raptor and treated with DMSO or rapamycin and a FITC-tagged antibody. Slope of a trend-line of fluorescence over forward scattering (FSC) was determined to discriminate fluorescence intensity from the effect of cell size (shown is the result of one of two independent experiments, 10,000 cells were counter before gating). (B) HCA2 cells were infected with a lentivirus expressing shRNA against IL-1 α and the relative IL-1 α mRNA level was measured. Shown is one representative of two independent experiments, each with triplicate samples. Raw data could be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Figure 8 Translation status of various transcripts after rapamycin treatment.

(A) After IR, senescent (Sen (IR)) HCA2 cells were treated for 1 day with rapamycin or DMSO followed by 1 day in serum-free media, after which cells were harvested and mRNA collected for polysome profiling. qPCR was performed on each fraction for IL1A, IL1B, IL6, IL8, IL3, IL5, TIMP1, CCL13 and TUBA1A mRNA (one representative experiment is shown). Fractions 1–7: Free RNA; 8–12: 40-60S; 13–20: polysomes. (B) NS or senescent (Sen (IR)) HCA2 cells were cultured for 7 days and then treated with DMSO or rapamycin for 4 h, after which cells were harvested and mRNA collected for polysome profiling. qPCR was performed on each fraction for IL1A, TUBA1A, IL6, and EEF2 mRNA (one representative experiment is shown). Fractions 1–4: Free RNA; 5–6: 40-60S; 7–11: polysomes. Right panel: polysome profiles used to determine the translated fractions. All polysome profile data are based on at least two independent replicates; representative polysome traces are shown. Raw data could be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Figure 9 MTORC1 inhibition does not reverse the senescence growth arrest.

(A) Effect of rapamycin on the number of senescent cells with detectable senescence-associated β-gal (SA-β-gal) activity. (B) Proliferative potential of PSC27 fibroblasts was measured under the indicated culture conditions. (C) PSC27 cells, NS or made senescent by IR and treated with DMSO or rapamycin for 6 days, were pulsed with BrdU for 24 h and the fraction that incorporated BrdU was determined by fluorescence microscopy. (D) SA-β-gal expression was determined for the cell populations described in Fig. 1 (one representative experiment is shown). (E) Clonogenic assays were performed on HCA2 cells to compare the effects of rapamycin and DMSO on NS cells or cells irradiated at 6, 8 or 10 Gy (one representative experiment is shown). (F) BJ and HCA2 human fibroblasts were irradiated at 5 or 10 Gy and clonogenic assays performed in the presence of DMSO or rapamycin (one representative experiment is shown). For panels A, B and C, shown is one representative of three independent experiments, each with triplicate cell culture samples. For panel D, E and F, shown is one clonogenic assay experiment replicated once. Raw data could be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Figure 10 Model for SASP suppression by rapamycin.

(1) Senescence signals activate IL-1α transcription; (2) IL-1α translation is MTOR-dependent and sensitive to rapamycin; (3) IL-1α at the plasma membrane binds the IL1R; (4) IL1R occupancy activates IL1R signaling; (5) IL1R signaling releases IκB, allowing NF-κB translocation to the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of genes encoding SASP factors; (6) SASP factors are transcribed, translated and secreted.

Supplementary Figure 11 Rapamycin suppresses tumour cell growth.

(A) Experimental timeline corresponding to Fig. 8a–c, e. (B) Experimental timeline corresponding to Fig. 8d. (C) PC3 prostate tumour cells were implanted subcutaneously with or without PSC27 prostate fibroblasts, and tumour sizes were measured every 2 weeks. PC3 cells were either exposed to DMSO or rapamycin ex vivo before implantation. PSC27 cells were exposed to ionizing radiation (IR), rapamycin (Rapa) or both ex vivo before implantation (n = 8 per type of treatment). (D) Timeline corresponding to the cell culture experiment presented in Fig. 8f. (E) Timeline corresponding to the in vivo experiment presented in Fig. 8f. Scheduled timing of mitoxantrone given as 3 doses 2 weeks apart, and rapamycin given every 2 days, to SCID mice over the course of an 8 week regimen. The mice were engrafted with PC3 cells alone, or combined with either PSC27-NS (control fibroblasts, without pre-treatment) or PSC27-Sen (IR) (fibroblasts pretreated with IR in culture). At the end of the treatment period, tumours were excised and volumes were determined, with 8-10 mice used per treatment arm. (F) PC3 prostate tumour cells were implanted subcutaneously with or without PSC27 prostate fibroblasts. After 2 weeks of tumour growth, mice were treated with vehicle (control), rapamycin (Rapa) and/or mitoxantrone (MIT). Tumour sizes were measured every 2 weeks (n = 10 per type of treatment). (G) (1) Tumour cells (orange) are surrounded by stromal cells (grey); (2) Treatment with DNA-damaging chemotherapy induces senescence in the stroma (blue cell). The SASP (red arrows) from these senescent cells fuels the proliferation of the remaining tumour cells; (3) Rapamycin reduces the intensity of the SASPs induced by chemotherapy, and tumour cell proliferation is decreased.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 2478 kb)

Supplementary Table 4

Supplementary Information (XLSX 99 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laberge, RM., Sun, Y., Orjalo, A. et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol 17, 1049–1061 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3195

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3195

This article is cited by

-

Inhibition of S6K lowers age-related inflammation and increases lifespan through the endolysosomal system

Nature Aging (2024)

-

Judith Campisi (1948–2024)

Nature Reviews Cancer (2024)

-

Lysosomal control of senescence and inflammation through cholesterol partitioning

Nature Metabolism (2023)

-

Cathepsin F is a potential marker for senescent human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes associated with skin aging

GeroScience (2023)

-

Mesenchymal stromal cell senescence in haematological malignancies

Cancer and Metastasis Reviews (2023)