Abstract

Response rate and toxicity of second-line therapy with docetaxel (75 mg m−2) or docetaxel, irinotecan, and lenogastrim (60 mg m−2, 200 mg m−2, and 150 μg m−2 day−1, respectively) were compared in 108 patients with stage IIIb–IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Addition of irinotecan to docetaxel does not improve response rate, and increases gastrointestinal toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Souquet et al, 1993; Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group, 1995; Cullen et al, 1999; Anderson et al, 2000; Ranson et al, 2000; Schiller et al, 2002). Since two trials demonstrated clinically beneficial effects of docetaxel in second-line setting (Fossella et al, 2000; Shepherd et al, 2000), docetaxel 75 mg m−2 is currently considered the standard regimen to which other experimental schedules should be compared.

Irinotecan, a semisynthetic water-soluble analogue of camptothecin, has shown activity in NSCLC patients as single agent and in combination with docetaxel (Fukuoka et al, 1992; Adjei et al, 2000; Masuda et al, 2000; Satouchi et al, 2001; Negoro et al, 2003). Moreover, Irinotecan demonstrated activity as single agent in pretreated patients (Sanchez et al, 2003). In our trial the efficacy of the combination of docetaxel and irinotecan compared to single-agent docetaxel as second-line treatment in NSCLC was investigated. Primary end point of this randomised phase II study was tumour response rate. Secondary end points were toxicity, progression-free survival and overall survival. The treatment regimen was based on a phase II study, which demonstrated activity of docetaxel and irinotecan in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer (Mäenpää et al, 1999). In this study, neutropenia was the main toxicity; therefore, we added a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to our treatment regimen.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

Inclusion criteria for enrolment in the trial were age ⩾18 years, stage IIIb–IV NSCLC, failure or relapse after first-line chemotherapy, at least one measurable or evaluable tumour lesion, performance status ⩽2 according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale, life expectancy of ⩾3 months, adequate bone marrow reserve (neutrophils ⩾1.5 × 109 l−1, platelets ⩾100 × 109 l−1, haemoglobin ⩾6.2 mmol l−1), renal function (serum creatinine ⩽1.25 times the upper normal limit), and liver function (serum bilirubin⩽the upper limit of the institutional reference value, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) and serum aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) ⩽2.5 times the upper normal limit, alkaline phosphatase ⩽5 times the upper normal limit). Prior radiotherapy was allowed as long as the irradiated area did not contain the sole measurable or evaluable lesion. Exclusion criteria were active infection, second primary malignancies (except carcinoma in situ of the cervix, adequately treated basal cell carcinoma of the skin, and other cancer curatively treated without recurrence for at least 5 years), symptomatic brain metastases, inflammatory bowel diseases, symptomatic peripheral neuropathy ⩾grade 2 according to the Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) of the National Cancer Institute (version 2.0), serious cardiac diseases, contraindications for use of corticosteroids, pregnancy, breast-feeding, or reproductive potential without implementing adequate contraceptive measures. Local medical ethics committees of all hospitals approved the protocol. All patients gave informed consent.

Treatment

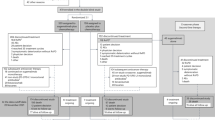

Patients were randomised by block randomisation to receive either docetaxel 75 mg m−2 on day 1 (D arm) or docetaxel 60 mg m−2 and irinotecan 200 mg m−2 both on day 1 followed by lenogastrim 150 μg m−2 day−1 on days 2–12 (DI arm). Docetaxel (in 250 ml 0.9% NaCl) was administered as a 1-h intravenous infusion in both treatment arms. Irinotecan (3 mg ml−1, diluted with 0.9% NaCl) was administered after docetaxel as a 90-min infusion. Lenogastrim ampoules contained 263 μg recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor dissolved in 1 ml solvent for subcutaneous injection. Treatment was repeated every 3 weeks for a maximum of five cycles and halted in case of tumour progression, intolerable toxicity or patient's wish. To prevent hypersensitivity reactions caused by docetaxel dexamethason 8 mg was given twice a day during 3 subsequent days starting the day before infusion. Antiemetics consisted of ondansetron 8 mg twice a day on days 1–3. In case of diarrhoea, patients were treated with loperamide (starting dose 4 mg, followed by 2 mg every 2 h as long as diarrhoea continued, maximum dose 16 mg per day). When the diarrhoea persisted for more than 48 h or occurred in combination with neutropenia, fever or dehydration, patients were hospitalised and treated with antibiotics.

Dose adjustments

Drug administration was postponed (maximally 2 weeks) if there was no haematologic recovery on day 22 (leukocytes <3.0 × 109 l−1 and/or platelets <100 × 109 l−1). In case of nadir values of neutrophils <0.5 × 109 l−1 or platelets <50 × 109 l−1 exceeding 7 days, febrile neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia associated with bleeding, the dose of docetaxel for subsequent cycles was reduced to 55 mg m−2 in the D arm and to 45 mg m−2 in the DI arm. The dose of irinotecan was reduced to 150 mg m−2 in these cases. In the event of grade 3–4 nonhaematologic toxicity (except nausea and vomiting) or grade 2 neuropathy, the doses of docetaxel and irinotecan were reduced with 25% for subsequent cycles. Treatment was stopped if the same severity of toxicity occurred at the reduced dose level treatment or in case of grade 3–4 neuropathy. In case of grade 3–4 diarrhoea lasting more than 2 weeks despite appropriate therapy, no further irinotecan was administered.

Treatment evaluation

Complete blood cell counts were performed weekly during treatment. On day 1 of each cycle, patient evaluation also included liver and renal functions, performance status, chest X-ray, and toxicity scoring according to CTC. All patients were evaluable for toxicity. Tumour response was evaluated according to World Health Organisation criteria (1979).

After discontinuation of treatment, physical examination, laboratory tests, chest X-ray, and additional imaging tests on clinical indication to assess tumour progression were performed every 6 weeks.

Statistical analysis

The ‘pick the winner’ format based on the randomised phase II clinical trials approach as proposed by Simon et al (1985) was used. In this approach, an accrual of 53 patients in each arm gives a 90% chance of selecting the better treatment schedule if the difference in response rate is at least 10% and the smaller response rate is assumed to be approximately 15%. The arm with the highest response rate is declared the ‘winner’ providing that the response rate is at least 15%. A statistically significant difference in response rate is not required in this trial design. This trial design is not suitable to test hypotheses of equality of effects. Moreover, with this approach, a treatment can still be selected even if the difference in response rate is less than 10%, but then the probability of correct selection will not be as great as 90%.

In order to terminate an ineffective schedule early in the study a three-stage stopping rule was used, as proposed earlier by Hoskins et al (1998). The conclusion from this study would be based on the ranking of the response rate. No formal statistical comparison between the two arms was planned for the primary end point.

Patient characteristics, treatment parameters, and toxicity in both arms were compared using Student's t-test, Mann–Whitney test, χ2 test, or Fisher's exact test. The time from the date of randomisation to the date of first documented progression was defined as progression-free survival. Overall survival was defined as the interval between the date of randomisation and the date of death. Survival data were compared by Kaplan–Meier curves using the log-rank test. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between October 2000 and January 2003, 108 patients from five hospitals in the Netherlands were randomised to D (n=56) or DI (n=52). Patient characteristics were not significantly different between both treatment arms (Table 1).

Toxicity

Haematologic toxicity is shown in Table 2. In the D arm, grade 3 or 4 leukopenia and granulocytopenia occurred more frequently as compared to the DI arm. However, in both arms, an equal number of patients was hospitalised for febrile neutropenia. Significantly more patients in the DI arm had thrombocytopenia. Anaemia occurred in both arms at equal frequency. At the time of study, erythropoietin was not routinely administered.

The worst nonhaematologic toxicity per patient is listed in Table 3. Diarrhoea was more frequently observed in the DI arm (P<0.01). In this arm, six patients were hospitalised for serious diarrhoea compared to one patient in the D arm (P=0.05). Nail changes and arthralgia were only observed in the D arm, where the higher docetaxel dose was administered. Additionally, significantly more patients in the D arm had myalgia (P<0.05).

Treatment

A total of 206 and 162 cycles were administered in the D and DI arm, respectively. The median (range) number of cycles per patient was 4 (1–5) in the D arm, and 3 (1–5) in the DI arm. The maximum of five cycles was completed in 25 (45%) patients in the D arm and in 17 (33%) patients in the DI arm (P>0.05). The reasons for treatment discontinuation for both arms were not different. Main reasons for treatment discontinuation were progressive disease and toxicity. Seven patients died due to disease progression while on protocol therapy. Three patients died due to toxicity of treatment, due to paralytic ileus after one cycle (n=1; D arm), bowel perforation after two cycles (n=1; DI arm), and myocardial infarction after one cycle (n=1; DI arm). Doses of docetaxel (D arm), docetaxel (DI arm), and irinotecan had to be reduced in 4, 2, and 7% of the cycles, respectively. In both arms, drug administration was postponed up to 2 weeks in 2% of the cycles.

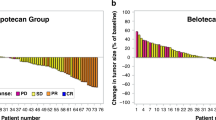

Tumour response

At the end of the first stage, one response was observed in the D arm vs two in the DI arm. A total of five responses was observed in both arms at the end of the second stage. Subsequently, enrolment continued to a total of 108 patients. Final analysis revealed an overall response rate of 16% (95% CI, 6–26) for the D arm and 10% (95% CI, 2–18) for the DI arm (Table 4). According to the statistical design of this trial, the D arm was declared the ‘winner’. Nine patients were not evaluable for tumour response due to early death (n=1; D arm, n=2; DI arm), discontinuation of treatment at patients request (n=1; D arm), and discontinuation for toxicity (n=5; DI arm). These patients were considered nonresponders.

Progression-free survival and overall survival

In August 2003, 22 patients were still alive. The median progression-free survival was not significantly different between both treatment arms; 18 (95% CI, 16–21) vs 15 (95% CI, 12–18) weeks for the D and DI arm, respectively (P=0.42) (Figure 1). The median overall survival was 32 (95% CI, 25–40) weeks in the D arm, vs 27 (95% CI, 8–46) weeks in the DI arm, which was not different between both arms (P=0.69). The 1-year survival rate (±s.e.) was 26% (±6%) vs 30% (±7%) in the D and DI arm, respectively (P=0.49) (Figure 2).

Discussion

According to the statistical design of this trial, the docetaxel arm, with a response rate of 16%, ranked superior compared to the docetaxel–irinotecan arm, with a response rate of 10%. Using this design, smaller number of patients are required compared to the usual randomised trial design in which sample size calculations are based on statistical significance. The conclusion of this trial – that addition of irinotecan to docetaxel as second-line chemotherapy in NSCLC does not improve response rate – is solely based on the ranking of response rate. Although our trial was not powered to detect differences in survival, the efficacy of docetaxel as single agent and docetaxel combined with irinotecan seemed not different in terms of progression-free survival and overall survival.

Both arms showed a different toxicity profile. Leukopenia, nail changes, myalgia, and arthralgia occurred more frequently in the D arm, while thrombocytopenia and diarrhoea were more common in the DI arm. Toxicities especially occurring in the D arm might probably be related to the higher dose level of docetaxel used in this arm. Nevertheless, toxicity in the docetaxel arm was acceptable. As in other trials, diarrhoea frequently occurred after treatment with docetaxel and irinotecan (Adjei et al, 2000; Masuda et al, 2000; Satouchi et al, 2001). In the majority of patients, in this trial, diarrhoea resolved after treatment with loperamide. An option for prevention of delayed-type diarrhoea (occurring >24 h after irinotecan administration) is administration of the poorly absorbed aminoglycoside antibiotic neomycin, which decreases the intestinal SN-38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) concentration by inhibition of β-glucuronidase activity from intestinal microflora (Kehrer et al, 2001).

The response rate for docetaxel monotherapy found in this trial is comparable to results of other phase II trials, which found a response rate between 16–22% (Fossella et al, 1995; Gandara et al, 2000; Robinet et al, 2000). In two phase III trials a lower response rate (7–11%) was reported (Fossella et al, 2000; Shepherd et al, 2000). Median survival for docetaxel monotherapy in our study was 7.5 months. The two mentioned phase III trials reported a median survival of 7.5 and 5.7 months, respectively (Fossella et al, 2000; Shepherd et al, 2000).

Two other single agents were recently investigated in a second-line setting in NSCLC patients. Gefitinib, an orally active EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was studied in a randomised phase II trial (Fukuoka et al, 2003). Antitumour activity, with a response rate between 18 and 19%, as well as symptom relief and improvement in quality of life was reported. Median survival was between 7.6 and 8.0 months. Pemetrexed, a novel multitargeted antifolate, was compared to single-agent docetaxel in a recently published phase III trial (Hanna et al, 2004). No significant differences in response rate and survival were found between patients in both arms. Response rate and survival were in accordance with other data on single-agent docetaxel as second-line treatment (Fossella et al, 2000; Shepherd et al, 2000). However, in the pemetrexed arm less toxicity, especially febrile neutropenia, was observed. Therefore, pemetrexed can probably be used as alternative reference regimen in the second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Whether combinations are superior to single agents in second-line setting is presently unclear. Although this trial demonstrated no clear benefit using docetaxel with irinotecan, other regimens using the combination of these drugs with filgrastrim support or with celecoxib are currently under investigation (Argiris, 2003; Frasci et al, 2004).

In conclusion, addition of irinotecan to docetaxel as second-line chemotherapy does not improve response rate, and increases gastrointestinal toxicity in patients with stage IIIb or IV NSCLC.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Adjei AA, Klein CE, Kastrissios H, Goldberg RM, Alberts SR, Pitot HC, Sloan JA, Reid JM, Hanson LJ, Atherton P, Rubin J, Erlichman C (2000) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of irinotecan and docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors: preliminary evidence of clinical activity. J Clin Oncol 18: 1116–1123

Anderson H, Hopwood P, Stephens RJ, Thatcher N, Cottier B, Nicholson M, Milroy R, Maughan TS, Falk SJ, Bond MG, Burt PA, Connolly CK, McIllmurray MB, Carmichael J (2000) Gemcitabine plus best supportive care (BSC) vs BSC in inoperable non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial with quality of life as the primary outcome. Br J Cancer 83: 447–453

Argiris A (2003) Celecoxib combined with weekly irinotecan (CPT-11) and docetaxel for the treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 41(Suppl 2): S179

Cullen MH, Billingham LJ, Woodroffe CM, Chetiyawardana AD, Gower NH, Joshi R, Ferry DR, Rudd RM, Spiro SG, Cook JE, Trask C, Bessell E, Connolly CK, Tobias J, Souhami RL (1999) Mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin in unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer: effects on survival and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 17: 3188–3194

Fossella FV, Devore R, Kerr RN, Crawford J, Natale RR, Dunphy F, Kalman L, Miller V, Lee JS, Moore M, Gandara D, Karp D, Vokes E, Kris M, Kim Y, Gamza F, Hammershaimb L (2000) Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel vs vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 18: 2354–2362

Fossella FV, Lee JS, Shin DM, Calayag M, Huber M, Perez-Soler R, Murphy WK, Lippman S, Benner S, Glisson B (1995) Phase II study of docetaxel for advanced or metastatic platinum-refractory non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 13: 645–651

Frasci G, Comella P, Thomas R, Di Bonito M, Lapenta L, Capasso I, Botti G, Vallone P, De RV, D'Aiuto G, Comella G (2004) Biweekly docetaxel–irinotecan with filgrastim support in pretreated breast and non-small-cell lung cancer patients. A phase I study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 53: 25–32

Fukuoka M, Niitani H, Suzuki A, Motomiya M, Hasegawa K, Nishiwaki Y, Kuriyama T, Ariyoshi Y, Negoro S, Masuda N (1992) A phase II study of CPT-11, a new derivative of camptothecin, for previously untreated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 10: 16–20

Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, Nishiwaki Y, Vansteenkiste J, Kudoh S, Rischin D, Eek R, Horai T, Noda K, Takata I, Smit E, Averbuch S, Macleod A, Feyereislova A, Dong RP, Baselga J (2003) Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 21: 2237–2246

Gandara DR, Vokes E, Green M, Bonomi P, Devore R, Comis R, Carbone D, Karp D, Belani C (2000) Activity of docetaxel in platinum-treated non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a phase II multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol 18: 131–135

Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, Von Pawel J, Gatzemeier U, Tsao TC, Pless M, Muller T, Lim HL, Desch C, Szondy K, Gervais R, Shaharyar, Manegold C, Paul S, Paoletti P, Einhorn L, Bunn Jr PA (2004) Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed vs docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 22: 1589–1597

Hoskins P, Eisenhauer E, Beare S, Roy M, Drouin P, Stuart G, Bryson P, Grimshaw R, Capstick V, Zee B (1998) Randomized phase II study of two schedules of topotecan in previously treated patients with ovarian cancer: a National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study. J Clin Oncol 16: 2233–2237

Kehrer DF, Sparreboom A, Verweij J, de Bruijn P, Nierop CA, van de SJ, Ruijgrok EJ, de Jonge MJ (2001) Modulation of irinotecan-induced diarrhea by cotreatment with neomycin in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 7: 1136–1141

Mäenpää J, Käär K, Kivinen S, Pohto M, Jekunen A (1999) Docetaxel and CPT-11 for recurrent ovarian cancer. A Phase II Study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 18: 363a

Masuda N, Negoro S, Kudoh S, Sugiura T, Nakagawa K, Saka H, Takada M, Niitani H, Fukuoka M (2000) Phase I and pharmacologic study of docetaxel and irinotecan in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 18: 2996–3003

Negoro S, Masuda N, Takada Y, Sugiura T, Kudoh S, Katakami N, Ariyoshi Y, Ohashi Y, Niitani H, Fukuoka M (2003) Randomised phase III trial of irinotecan combined with cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 88: 335–341

Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group (1995) Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. BMJ 311: 899–909

Ranson M, Davidson N, Nicolson M, Falk S, Carmichael J, Lopez P, Anderson H, Gustafson N, Jeynes A, Gallant G, Washington T, Thatcher N (2000) Randomized trial of paclitaxel plus supportive care vs supportive care for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1074–1080

Robinet G, Thomas P, Perol M, Vergnenegre A, Lena H, Taytard A, Paillotin D, Bessa EH, Schuller-Lebeau MP (2000) Efficacy of docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer patients previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy. French Group of Pneumo-Cancerology. Rev Mal Respir 17: 83–89

Sanchez R, Esteban E, Palacio I, Fernandez Y, Muniz I, Vieitez JM, Fra J, Blay P, Villanueva N, Una E, Mareque B, Estrada E, Buesa JM, Lacave AJ (2003) Activity of weekly irinotecan (CPT-11) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer pretreated with platinum and taxanes. Invest New Drugs 21: 459–463

Satouchi M, Takada Y, Takeda K, Yamamoto N, Negoro S, Nakagawa K, Matsui K, Kawahara M, Fukuoka M, Ariyoshi H (2001) Randomized phase II Study of docetaxel plus cisplatin vs docetaxel plus irinotecan in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); A West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group (WJTOG) Study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 20: 329a

Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH (2002) Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 346: 92–98

Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, Levitan N, Gressot L, Vincent M, Burkes R, Coughlin S, Kim Y, Berille J (2000) Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel vs best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 18: 2095–2103

Simon R, Wittes RE, Ellenberg SS (1985) Randomized phase II clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rep 69: 1375–1381

Souquet PJ, Chauvin F, Boissel JP, Cellerino R, Cormier Y, Ganz PA, Kaasa S, Pater JL, Quoix E, Rapp E (1993) Polychemotherapy in advanced non small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet 342: 19–21

World Health Organisation (1979) WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Aventis Pharma, Hoevelaken, the Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wachters, F., Groen, H., Biesma, B. et al. A randomised phase II trial of docetaxel vs docetaxel and irinotecan in patients with stage IIIb–IV non-small-cell lung cancer who failed first-line treatment. Br J Cancer 92, 15–20 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602268

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602268

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phase II study of amrubicin plus erlotinib in previously treated, advanced non-small cell lung cancer with wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor (TORG1320)

Investigational New Drugs (2021)

-

Comparison between single-agent and combination chemotherapy as second-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective analysis

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2020)

-

The efficacy and safety of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab in previously treated patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (ns-NSCLC)

Tumor Biology (2015)

-

Pharmacoethnicity of docetaxel-induced severe neutropenia: integrated analysis of published phase II and III trials

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2013)

-

Phase I/II study of amrubicin in combination with S-1 as second-line chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer without EGFR mutation

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2013)