Abstract

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a potentially life-threatening heart disease emerging toward the end of pregnancy or in the first postpartal months in previously healthy women. Recent data suggest a central role of unbalanced peri-/postpartum oxidative stress that triggers the proteolytic cleavage of the nursing hormone prolactin (PRL) into a potent antiangiogenic, proapoptotic, and proinflammatory 16-kDa PRL fragment. This notion is supported by the observation that inhibition of PRL secretion by bromocriptine, a dopamine D2-receptor agonist, prevented the onset of disease in an animal model of PPCM and by first clinical experiences where bromocriptine seem to exert positive effects with respect to prevention or treatment of PPCM patients. Here, we highlight the current state of knowledge on diagnosis of PPCM, provide insights into the biology and pathophysiology of 16-kDa PRL and bromocriptine, and outline potential consequences for the clinical management and treatment options for PPCM patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance•• Of major importance

•• Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Petrie MC, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:767–78. This position paper of the ESC study group of peripartum cardiomyopathy summarizes the current knowledge with regard to definition, etiology, and treatment of peripartum cardiomyopathy..

Pearson GD, Veille JC, Rahimtoola S, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. 2000;283:1183–8.

Sliwa K, Fett J, Elkayam U. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2006;368:687–93.

Brar SS, Khan SS, Sandhu GK, et al. Incidence, mortality, and racial differences in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:302–4.

Fett JD. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Insights from Haiti regarding a disease of unknown etiology. Minn Med. 2002;85:46–8.

Fett JD, Christie LG, Carraway RD, Murphy JG. Five-year prospective study of the incidence and prognosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy at a single institution. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1602–6.

Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, Borghi C, et al. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:3147–97.

Duran N, Gunes H, Duran I, et al. Predictors of prognosis in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101:137–40.

Sliwa K, Forster O, Libhaber E, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: inflammatory markers as predictors of outcome in 100 prospectively studied patients. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:441–6.

Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaminski K, Podewski E, et al. A Cathepsin D-Cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy. Cell. 2007;128:589–600.

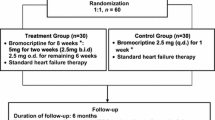

•• Sliwa K, Blauwet L, Tibazarwa K, et al. Evaluation of bromocriptine in the treatment of acute severe peripartum cardiomyopathy: a proof-of-concept pilot study. Circulation. 2010;121:1465–73. This was the first small randomized trial in a PPCM patient collective in South Africa, and suggested a major beneficial effect of bromocriptine to improve recovery from PPCM..

Gonzalez C, Parra A, Ramirez-Peredo J, et al. Elevated vasoinhibins may contribute to endothelial cell dysfunction and low birth weight in preeclampsia. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1009–17.

Tabruyn SP, Nguyen NQ, Cornet AM, et al. The antiangiogenic factor, 16-kDa human prolactin, induces endothelial cell cycle arrest by acting at both the G0-G1 and the G2-M phases. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1932–42.

Tabruyn SP, Sabatel C, Nguyen NQ, et al. The angiostatic 16 K human prolactin overcomes endothelial cell anergy and promotes leukocyte infiltration via NF-{kappa}B activation. Mol Endocrinol 2007.

Tabruyn SP, Sorlet CM, Rentier-Delrue F, et al. The antiangiogenic factor 16 K human prolactin induces caspase-dependent apoptosis by a mechanism that requires activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1815–23.

Demakis JG, Rahimtoola SH. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1971;44:964–8.

Selle T, Renger I, Labidi S, et al. Reviewing peripartum cardiomyopathy: current state of knowledge. Future Cardiol. 2009;5:175–89.

Goland S, Modi K, Bitar F, et al. Clinical profile and predictors of complications in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2009;15:645–50.

Tibazarwa K, Lee G, Mayosi B, et al. The 12-lead ECG in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23:1–8.

Forster O, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Ansari AA, et al. Reversal of IFN-gamma, oxLDL and prolactin serum levels correlate with clinical improvement in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:861–8.

Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: A JACC White Paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1475–87.

Karamitsos TD, Neubauer S. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a powerful diagnostic and prognostic tool in modern cardiology. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;54:179–80.

Leurent G, Baruteau AE, Larralde A, et al. Contribution of cardiac MRI in the comprehension of peripartum cardiomyopathy pathogenesis. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:e91–3.

Kawano H, Tsuneto A, Koide Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Intern Med. 2008;47:97–102.

Mouquet F, Lions C, de Groote P, et al. Characterisation of peripartum cardiomyopathy by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2765–9.

Pearl W. Familial occurrence of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 1995;129:421–2.

Pierce JA, Price BO, Joyce JW. Familial occurrence of postpartal heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1963;111:651–5.

Meyer GP, Labidi S, Podewski E, et al. Bromocriptine treatment associated with recovery from peripartum cardiomyopathy in siblings: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:80.

Fett JD, Sundstrom BJ, Etta King M, Ansari AA. Mother-daughter peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86:331–2.

van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, van Tintelen JP, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy as a part of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;121:2169–75.

Morales A, Painter T, Li R, et al. Rare variant mutations in pregnancy-associated or peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;121:2176–82.

Bahl A, Swamy A, Sharma Y, Kumar N. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricle presenting as peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2006;109:422–3.

Lea B, Bailey AL, Wiisanen ME, et al. Left ventricular noncompaction presenting as peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2012;154:e65–6.

Rehfeldt KH, Pulido JN, Mauermann WJ, Click RL. Left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction in a patient with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:e18–20.

Paterick TE, Gerber TC, Pradhan SR, et al. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy: what do we know? Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2010;11:92–9.

Frischknecht BS, Attenhofer Jost CH, Oechslin EN, et al. Validation of noncompaction criteria in dilated cardiomyopathy, and valvular and hypertensive heart disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:865–72.

Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, et al. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990;82:507–13.

Stollberger C, Finsterer J. Trabeculation and left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:1120–1. aothor reply 1121.

Probst S, Oechslin E, Schuler P, et al. Sarcomere gene mutations in isolated left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy do not predict clinical phenotype. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:367–74.

Hoedemaekers YM, Caliskan K, Michels M, et al. The importance of genetic counseling, DNA diagnostics, and cardiologic family screening in left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:232–9.

Walenta K, Schwarz V, Schirmer SH, et al. Circulating microparticles as indicators of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2012.

Leanos-Miranda A, Marquez-Acosta J, Cardenas-Mondragon GM, et al. Urinary prolactin as a reliable marker for preeclampsia, its severity, and the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2492–9.

Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Baltabaeva A, et al. Maternal cardiac dysfunction and remodeling in women with preeclampsia at term. Hypertension. 2011;57:85–93.

Lkhider M, Castino R, Bouguyon E, et al. Cathepsin D released by lactating rat mammary epithelial cells is involved in prolactin cleavage under physiological conditions. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5155–64.

Ferrara N, Clapp C, Weiner R. The 16 K fragment of prolactin specifically inhibits basal or fibroblast growth factor stimulated growth of capillary endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 1991;129:896–900.

Piwnica D, Touraine P, Struman I, et al. Cathepsin D processes human prolactin into multiple 16 K-like N-terminal fragments: study of their antiangiogenic properties and physiological relevance. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2522–42.

Clapp C, Weiner RI. A specific, high affinity, saturable binding site for the 16-kilodalton fragment of prolactin on capillary endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 1992;130:1380–6.

D’Angelo G, Martini JF, Iiri T, et al. 16 K human prolactin inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced activation of Ras in capillary endothelial cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:692–704.

Lee SH, Kunz J, Lin SH, Yu-Lee LY. 16-kDa prolactin inhibits endothelial cell migration by down-regulating the Ras-Tiam1-Rac1-Pak1 signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11045–53.

Gonzalez C, Corbacho AM, Eiserich JP, et al. 16 K-prolactin inhibits activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, intracellular calcium mobilization, and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5714–22.

Nguyen NQ, Cornet A, Blacher S, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis establishment by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer delivery of the antiangiogenic factor 16 K hPRL. Mol Ther. 2007;15:2094–100.

Kinet V, Castermans K, Herkenne S, et al. The angiostatic protein 16 K human prolactin significantly prevents tumor-induced lymphangiogenesis by affecting lymphatic endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4062–71.

• Kinet V, Nguyen NQ, Sabatel C, et al. Antiangiogenic liposomal gene therapy with 16 K human prolactin efficiently reduces tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2009;284:222–8. This study describes potential beneficial effects of 16-kDa prolactin in the treatment of cancer..

Pan H, Nguyen NQ, Yoshida H, et al. Molecular targeting of antiangiogenic factor 16 K hPRL inhibits oxygen-induced retinopathy in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2413–9.

Duenas Z, Rivera JC, Quiroz-Mercado H, et al. Prolactin in eyes of patients with retinopathy of prematurity: implications for vascular regression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2049–55.

Garcia C, Aranda J, Arnold E, et al. Vasoinhibins prevent retinal vasopermeability associated with diabetic retinopathy in rats via protein phosphatase 2A-dependent eNOS inactivation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2291–300.

Habedank D, Kuhnle Y, Elgeti T, et al. Recovery from peripartum cardiomyopathy after treatment with bromocriptine. Eur J Heart Fail 2008.

Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Meyer GP, Schieffer E, et al. Recovery from postpartum cardiomyopathy in 2 patients by blocking prolactin release with bromocriptine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2354–5.

Reuwer AQ, Reuwer PJ, van der Post JA, et al. Prolactin fragmentation by trophoblastic matrix metalloproteinases as a possible contributor to peripartum cardiomyopathy and pre-eclampsia. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74:348–52.

Macotela Y, Aguilar MB, Guzman-Morales J, et al. Matrix metalloproteases from chondrocytes generate an antiangiogenic 16 kDa prolactin. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1790–800.

Holt RI, Barnett AH, Bailey CJ. Bromocriptine: old drug, new formulation and new indication. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:1048–57.

Kochenour NK. Lactation suppression. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23:1045–59.

Hopp L, Haider B, Iffy L. Myocardial infarction postpartum in patients taking bromocriptine for the prevention of breast engorgement. Int J Cardiol. 1996;57:227–32.

Y-Hassan S, Jernberg T. Bromocriptine-induced coronary spasm caused acute coronary syndrome, which triggered its own clinical twin–Takotsubo syndrome. Cardiology. 2011;119:1–6.

Khurana S, Liby K, Buckley AR, Ben-Jonathan N. Proteolysis of human prolactin: resistance to cathepsin D and formation of a nonangiostatic, C-terminal 16 K fragment by thrombin. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4127–32.

James AH, Brancazio LR, Ortel TL. Thrombosis, thrombophilia, and thromboprophylaxis in pregnancy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2005;3:187–97.

Goland S, Schwarz ER, Siegel RJ, Czer LS. Pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:e11–3.

Patti G, Nasso G, D’Ambrosio A, et al. Myocardial infarction during pregnancy and postpartum: a review. G Ital Cardiol. 1999;29:333–8.

Roth A, Elkayam U. Acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:171–80.

Bolyakov A, Paduch DA. Prolactin in men’s health and disease. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:527–34.

Erem C, Kocak M, Nuhoglu I, et al. Blood coagulation, fibrinolysis and lipid profile in patients with prolactinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73:502–7.

Bonuccelli U, Del Dotto P, Rascol O. Role of dopamine receptor agonists in the treatment of early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15 Suppl 4:S44–53.

Martinez-Martin P, Kurtis MM. Systematic review of the effect of dopamine receptor agonists on patient health-related quality of life. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15 Suppl 4:S58–64.

• Valiquette G. Bromocriptine for diabetes mellitus type II. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19:272–5. This study emphasizes positive effects of bromocriptine treatment in patients with diabetes mellitus type II..

Gaziano JM, Cincotta AH, O’Connor CM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of quick-release bromocriptine among patients with type 2 diabetes on overall safety and cardiovascular outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1503–8.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the National Research Foundation (NRF).

Disclosures

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hilfiker-Kleiner, D., Struman, I., Hoch, M. et al. 16-kDa Prolactin and Bromocriptine in Postpartum Cardiomyopathy. Curr Heart Fail Rep 9, 174–182 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-012-0095-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-012-0095-7